Beware the corporate or political interest that tells you any country, region, city, or industry would be better off with defunded and debilitated Earth observation satellite services or reduced staffing of weather services. While extreme weather events and natural disasters have become more frequent, severe, and costly, loss of life has declined in countries and regions where weather services, early warning, and disaster response, are more robust, precise, and effective.

It is easy to start taking for granted the importance of services that reduce harm and cost. The more successful they are, the more it seems we have overcome an existential threat. This allows those that are least studied in the relevant history, especially if they have never faced such peril themselves, to discount the foundational world-building value of those services.

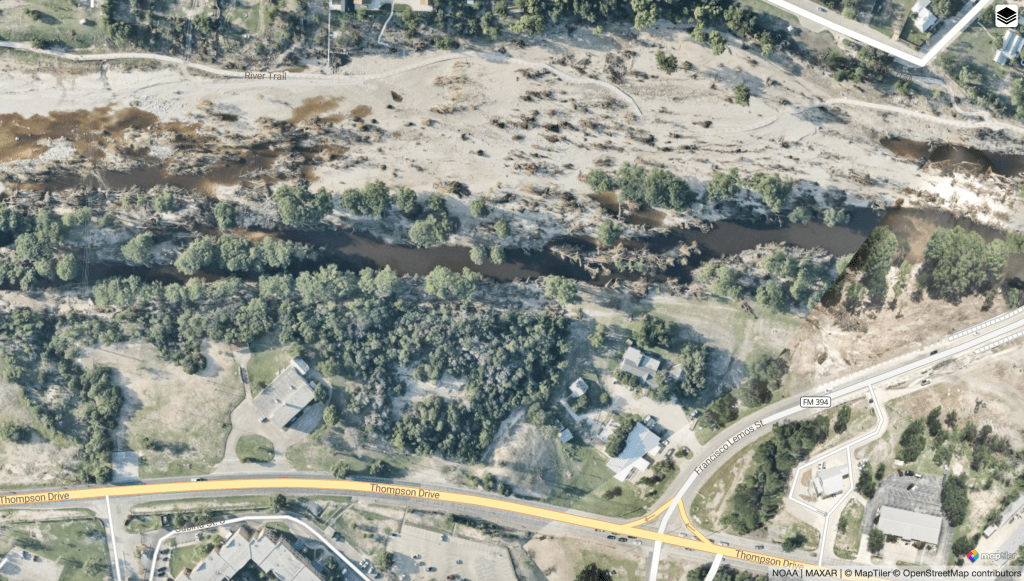

While forecasting had not yet broken down, the tragic July 4 floods along the Guadalupe River in central Texas show the immediate risk to human life from failure to spread warnings locally in the hours before maximum danger. Worse, emergency response services were gutted, as FEMA discontinued key contracts hours after the tragic floods struck. Those contracts were not reinstated for a week, during which time many of the most at risk survivors lost their last chance to be rescued.

In the days after the Guadalupe River disaster, flash floods struck Houston. In at least some areas, flash flood alerts went out to phones three hours after vehicles were already swamped and stalled by highway flooding. Underinvesting in weather and climate services, including early warning and local staffing and communications support, puts lives at risk and creates unnecessary disruption of basic services and everyday economic activity.

Just one week after the Guadalupe River disaster, while rescue efforts are still ongoing, northern and central Texas again experienced major flash flooding, leading to evacuations across several counties. One lawmaker asked the public to please take the order seriously, as waters were rising faster than during the July 4 floods.

As the Texas Tribune reports:

That weekend, the destructive, fast-moving waters rose 26 feet on the Guadalupe River in just 45 minutes before daybreak on July 4, washing away homes and vehicles. Ever since, searchers have used helicopters, boats and drones to look for victims and to rescue people stranded in trees and from camps isolated by washed-out roads.

While one of the dangerous, structural impacts of global climate disruption is drought—which can be more severe and prolonged than would otherwise be the case—it is also true that hotter air pulls more moisture from water bodies and can unleash sudden torrents of rain. The combination of dry ground and torrential rain leads to more catastrophic flooding events, and these are expected to become far more likely.

Climate observation and weather services—including local observers, data translators, and ground agents—are preconditions for prosperity, and for everyday safety and security. Local economies cannot function, and loss of life will hit more places, if such services are degraded, when they are needed more than ever.

The United States is experiencing unprecedented outbreaks of tornado weather, wildfires, torrential rains, and flash floods, because the atmosphere is hotter and holding more water. This pattern does not alleviate the trend toward more serious and more long-running dry conditions; it contributes to it, because moisture in the air is not in the soil, and dryer soil supports reduced soil ecology, which makes it harder to hold moisture.

Torrential rains and flash floods are also destructive to sensitive crops. Unless critical infrastructure and sustainable water and land use strategies are widespread in affected areas, these rainfall patterns will add to the risks affecting rural communities and the costs associated with responding to those risks.

Investors—whether operating through the public or private sectors—must consider this emerging structural risk: If climate and weather services are degraded, or lacking, there will be greater disruption and cost, including reduced access to insurance and a higher cost of capital.

No one has the luxury of treating this as someone else’s problem. Wherever this vulnerability exists, it must either be reduced, through targeted, multilevel climate and weather services, early warning systems, and sufficient ground operations to avoid disaster, or underinvestment will lead to worsening geophysical risk and the rising costs that come with it.

In the United States, between the middle of 2024 and early 2025, there were two extreme weather events (Hurricane Helene and the Los Angeles fires) which are estimated to have caused more than $250 billion over time. Both were made worse by global heating and climate disruption. Each of those events, on its own, will eventually cost more than all disasters in the United States exceeding $1 billion from 1980 through 1989, combined.

The scale of the challenges ahead is almost unimaginable. The 2023 State of the Climate report framed the world of disruption to come this way:

By the end of this century, an estimated 3 to 6 billion individuals — approximately one-third to one-half of the global population — might find themselves confined beyond the livable region, encountering severe heat, limited food availability, and elevated mortality rates because of the effects of climate change (Lenton et al. 2023).

We are living in a climate-altered future, where risk and resilience questions can carry dollar values far exceeding any entity’s budgetary means, with physical risk exceeding historically adequate preparedness measures. Achieving operational resilience and the conditions for sustainable prosperity requires best-in-class climate observation and weather services, with as robust as possible a local footprint, including observation, translation, early warning, and timely delivery of disaster prevention and response insights.